Intro to Optimizing Packages on Solus

We'll explore how to build packages with advanced compiler techniques in order to squeeze more performance out of the box for packages in Solus. We'll be using the story of how libwebp was optimized for and how it led to an unexpected side quest.

Linux distributions have a lot of control over how a source-based package gets compiled and shipped to users as part of a binary repository. Aggressive and advanced compiler optimization techniques, as well as other methods can be used to provide greater out of the box performance for end users. This can greatly benefit users running on older hardware to provide a snappier end-user experience; reducing time waiting on a heavy workload to finish; or even improved battery life; amongst other improvements.

Part of the problem is, a packager's time is limited. So how, as a distribution, do you choose to try provide faster compatible packages for an end user. A historic approach is to simply change the default compiler flags for all packages, such as enabling LTO by default. Whilst this approach can work well, at Solus the philosophy is slightly different where a packager can trivially enable several advanced compiler optimization techniques such as PGO without too much faffing around on a targeted package.

The benefits of such an approach are:

- Can target the performance of a specific package to benefit all users

- A compiler optimization may improve one package, but may not apply globally to all packages.

The downsides are such:

- Requires additional packager time to benchmark and experiment with different optimization strategies.

- Requires the packager to choose and invest time into improving performance of a package.

- Requires the packager to find an appropriate benchmark to test the package against.

- Experimenting with compiler optimizations may not bear fruit: no meaningful improvement in performance, or there may be some other bottleneck.

Optimization Techniques Available

- speed:

- As simple as it gets really, build a package with

-O3instead of-O2as well as any other flags deemed worthy to be included as part of thespeedflags. The main drawback of this is that-O3is not guaranteed to produce faster results than building with-O2and typically will produce bigger binaries. The days of-O3outright breaking your program in weird unexpected ways is largely behind us.

- As simple as it gets really, build a package with

- LTO:

- Compared to some other distributions

-fltois not yet enabled by default on Solus. LTO is almost guaranteed to provide a %1 or slightly larger performance improvement as well as a smaller binary at the cost of increased compiling times and memory usage during build. When combined with other optimization techniques such as PGO the LTO optimization can really stretch its legs and provide even greater uplift!

- Compared to some other distributions

- Clang:

- Not strictly an optimization, but, building a package with

clanginstead ofgccandld.lddto link instead of the infamousld.bfdmay provide a faster package out of the box. You'll have to be careful of subtle ABI differences if building withclang. If in doubt, and,clangis the obvious choice, perform safety rebuilds on all reverse dependencies of the package.

- Not strictly an optimization, but, building a package with

- PGO:

- Profile guided optimization. Build once with instrumentation in order to collect profile data when ran. Run the program using a representative workload in order to collect profiling data. Build the program again with the profiling data provided in order to build an optimized variant.

- BOLT:

- Binary optimization and layout tool. You can think of this as "post-link PGO" where you instrument a binary with

boltto collect profiling data. Run that binary. Then finally reorganize the binary layout using the collected profile data. This generally works better on large statically linked binaries but smaller binaries or libraries such as found in a typical package can benefit too. This optimization is still quite new.

- Binary optimization and layout tool. You can think of this as "post-link PGO" where you instrument a binary with

Regardless, that's enough word spaghetti, let's look at the process to actually optimize a package.

Optimizing a Package

Right, to begin with we'll have to start on choosing an actual package to benchmark and optimize. I've heard the .webp file format is becoming increasingly common on the web, slowly replacing .png and .jpg file formats due to the strong backing of Google (for better or for worst). An improvement in decoding time for .webp files would benefit any user using a web browser casually browsing the web.

Let's have a look at the package.yml build recipe for libwebp.

name : libwebp

version : 1.3.2

release : 25

source :

- https://github.com/webmproject/libwebp/archive/refs/tags/v1.3.2.tar.gz : c2c2f521fa468e3c5949ab698c2da410f5dce1c5e99f5ad9e70e0e8446b86505

homepage : https://developers.google.com/speed/webp/

license : BSD-3-Clause

component : multimedia.codecs

summary : A new image format for the web

description: |

WebP is a new image format that provides lossless and lossy compression for images on the web. WebP lossless images are 26% smaller in size compared to PNGs. WebP lossy images are 25-34% smaller in size compared to JPEG images at equivalent SSIM index. WebP supports lossless transparency (also known as alpha channel) with just 22% additional bytes. Transparency is also supported with lossy compression and typically provides 3x smaller file sizes compared to PNG when lossy compression is acceptable for the red/green/blue color channels.

emul32 : yes

patterns :

- devel : /usr/share/man

builddeps :

- pkgconfig32(glu)

- pkgconfig32(glut)

- pkgconfig32(libpng)

- pkgconfig32(libtiff-4)

- pkgconfig32(libturbojpeg)

- pkgconfig32(zlib)

- giflib-devel

setup : |

%reconfigure --disable-static --enable-everything

build : |

%make

install : |

%make_install

Okay, looks to be a quite simple affair. A simple configure, make, make install as well as emul32 being enabled specifying the -32bit packages are also provided from this recipe. Next step is to look for a repeatable and easy way to benchmark it. We'll begin by looking at the pspec_x86_64.xml file which lists all the files produced from the package.yml recipe as well as some metadata.

<Name>libwebp</Name>

<Summary xml:lang="en">A new image format for the web</Summary>

<Description xml:lang="en">WebP is a new image format that provides lossless and lossy compression for images on the web. WebP lossless images are 26% smaller in size compared to PNGs. WebP lossy images are 25-34% smaller in size compared to JPEG images at equivalent SSIM index. WebP supports lossless transparency (also known as alpha channel) with just 22% additional bytes. Transparency is also supported with lossy compression and typically provides 3x smaller file sizes compared to PNG when lossy compression is acceptable for the red/green/blue color channels.

</Description>

<PartOf>multimedia.codecs</PartOf>

<Files>

<Path fileType="executable">/usr/bin/cwebp</Path>

<Path fileType="executable">/usr/bin/dwebp</Path>

<Path fileType="executable">/usr/bin/gif2webp</Path>

<Path fileType="executable">/usr/bin/img2webp</Path>

<Path fileType="executable">/usr/bin/vwebp</Path>

<Path fileType="executable">/usr/bin/webpinfo</Path>

<Path fileType="executable">/usr/bin/webpmux</Path>

Perfect, we have dwebp and cwebp binaries available in the main package, which from a guess can be used to decode and encode .webp files. Let's try it out.

$ dwebp -h

Usage: dwebp in_file [options] [-o out_file]

Decodes the WebP image file to PNG format [Default].

Note: Animated WebP files are not supported.

$ cwebp -h

Usage:

cwebp [options] -q quality input.png -o output.webp

Awesome, these binaries do exactly what we need to benchmark libwebp, but, we are also indirectly testing libpng as well for this benchmark, we'll have to keep an eye out for that.

One extra step we have to do is ensure these binaries are actually linking against their own library, as upstream developers can have a habit of making sure their binaries don't link against their own libraries and end up being self-contained. Run ldd to verify.

$ ldd /usr/bin/dwebp

linux-vdso.so.1 (0x00007ffed8733000)

libwebpdemux.so.2 => /usr/lib/libwebpdemux.so.2.0.14 (0x00007f7473bb4000)

libwebp.so.7 => /usr/lib/libwebp.so.7.1.8 (0x00007f7473ae2000)

libpng16.so.16 => /usr/lib/libpng16.so.16 (0x00007f7473aa6000)

libc.so.6 => /usr/lib/glibc-hwcaps/x86-64-v3/libc.so.6 (0x00007f74738a9000)

libsharpyuv.so.0 => /usr/lib/libsharpyuv.so.0.0.1 (0x00007f747389e000)

libm.so.6 => /usr/lib/glibc-hwcaps/x86-64-v3/libm.so.6 (0x00007f74737b8000)

libz.so.1 => /usr/lib/libz.so.1.3.0 (0x00007f7473200000)

/usr/lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 (0x00007f7473bea000)

Awesome in this case both dwebp and cwebp link against libwebp.so so we can be confident that any performance improvements will be applicable to all packages in the repository linking against libwebp.

Let's grab a couple of .webp files from here to test with. We'll just use the largest image size available in this case to reduce noise as much as possible when running benchmarks as well as allow any potential optimizations to stretch their legs a little more.

Now having done the prep work, lets actually benchmark the damn thing using hyperfine for the time being.

$ hyperfine "dwebp ~/3.webp -o /dev/null"

Benchmark 1: dwebp ~/3.webp -o /dev/null

Time (mean ± σ): 202.2 ms ± 0.3 ms [User: 198.9 ms, System: 3.0 ms]

Range (min … max): 201.8 ms … 202.7 ms 14 runs

$ hyperfine "cwebp ~/PNG_Test.png -o /dev/null"

Benchmark 1: cwebp ~/PNG_Test.png -o /dev/null

Time (mean ± σ): 1.423 s ± 0.009 s [User: 1.346 s, System: 0.076 s]

Range (min … max): 1.410 s … 1.435 s 10 runs

There, we have our a basic baseline for encode and decode performance. We mostly care about decode performance here but improved encoding performance would also not go amiss.

Let's Start Obvious

Let's start basic, enabling the speed optimization which basically builds with -O3 instead of -O2 as well as any other flags that are deemed to be worthy to be part of the speed group. As well as, the lto optimization which builds with link time optimization allowing for inter-procedural optimizations to take place.

optimize:

- speed

- lto

Moment of truth...

$ hyperfine "dwebp ~/3.webp -o /dev/null"

Benchmark 1: dwebp ~/3.webp -o /dev/null

Time (mean ± σ): 200.0 ms ± 1.5 ms [User: 197.3 ms, System: 2.5 ms]

Range (min … max): 198.1 ms … 203.2 ms 15 runs

$ hyperfine "cwebp ~/PNG_Test.png -o /dev/null"

Benchmark 1: cwebp ~/PNG_Test.png -o /dev/null

Time (mean ± σ): 1.353 s ± 0.012 s [User: 1.281 s, System: 0.071 s]

Range (min … max): 1.336 s … 1.369 s 10 runs

Well okay, we got a very minor uplift in decoding performance and a slightly higher improvement in encoding performance, but nothing too much to write home about. Luckily we have several more optimizations to explore...

PGO is great, except, when it isn't.

Next step is to explore PGO (Profile Guided Optimization). For our libwebp package, looks like we already hit a bit of a snafu. There's no test suite included in the tarball! That's a bit of a disappointment as a test suite such as make check is by far and away the easiest and most comprehensive workload that can be used for profiling as part of PGO, especially for smaller libraries. However, we can still experiment with the just built dwebp and cwebp binaries as a suitable workload for PGO.

Luckily, as part of the package.yml format all you have to do is provide a profile for automatic PGO. After chrooting into the build environment and fiddling around a bit we end up with:

profile : |

./examples/dwebp webp_js/test_webp_js.webp -o test_png.png

./examples/cwebp test_png.png -o /dev/null

After specifying that, 6 builds will now be performed instead of 2:

- emul32:

- Instrumented build

- Run profiling workload

- Optimized build using profiling data

- x86_64:

- Instrumented build

- Run profiling workload

- Optimized build using profiling data

For this relatively small package it increases the build time from 1m1.672s to 1m42.199s

The next moment of truth...

$ hyperfine "dwebp ~/3.webp -o /dev/null"

Benchmark 1: dwebp ~/3.webp -o /dev/null

Time (mean ± σ): 204.1 ms ± 2.2 ms [User: 201.3 ms, System: 2.7 ms]

Range (min … max): 201.6 ms … 207.1 ms 14 runs

$ hyperfine "cwebp ~/PNG_Test.png -o /dev/null"

Benchmark 1: cwebp ~/PNG_Test.png -o /dev/null

Time (mean ± σ): 1.349 s ± 0.010 s [User: 1.266 s, System: 0.082 s]

Range (min … max): 1.335 s … 1.374 s 10 runs

Well... That's interesting. We actually regress in performance for decode performance whilst gaining another small bump in encoding performance. Worse still, we get a bunch of profile count data file not found [-Wmissing-profile] warning messages during the optimized build indicating to us our profiling workload isn't comprehensive enough and doesn't cover enough code paths. The lack of a handy make check that could be used as a profiling workload is really hurting us here. For now, let's put a pin in exploring PGO, it isn't a dead end but more work needs to be done curating a more comprehensive workload to chuck at it in this particular case, whilst other, easier, optimization techniques are still available to us.

256 Vector Units go brrrrrr...

The next obvious step is to explore glibc hardware capabilities. For those unaware both clang and gnu compilers provide x86_64-v2, x86_64-v3 and x86_64-v4 micro-architecture build options on top of the baseline of x86_64. These enable the use of targeting additional CPU instruction sets during compilation for better performance. For example, -sse4.2 for x86_64-v2, -avx2 for x86_64-v3, and -avx512 for x86_64-v4.

Whilst that's great 'n all, if a program is built with x86_64-v3 and gains an additional ~10% uplift in performance, it's no good if a x86_64-v2 compatible cpu can't run it. Luckily the glibc loader that's found on almost general purpose linux installs provides a way to load higher or lower micro-architecture libraries if they're installed and supported.

On top of all that, the package.yml format provides an incredibly simple way of providing x86_64-v3 built libraries by enabling the avx2 : yes flag.

With avx2 : yes enabled in the libwebp package three builds are performed.

- emul32

- x86_64-v3

- x86_64

We now see these additional files in the pspec_x86_64.xml file

+ <Path fileType="library">/usr/lib64/glibc-hwcaps/x86-64-v3/libsharpyuv.so.0</Path>

+ <Path fileType="library">/usr/lib64/glibc-hwcaps/x86-64-v3/libsharpyuv.so.0.0.1</Path>

+ <Path fileType="library">/usr/lib64/glibc-hwcaps/x86-64-v3/libwebp.so.7</Path>

+ <Path fileType="library">/usr/lib64/glibc-hwcaps/x86-64-v3/libwebp.so.7.1.8</Path>

+ <Path fileType="library">/usr/lib64/glibc-hwcaps/x86-64-v3/libwebpdecoder.so.3</Path>

+ <Path fileType="library">/usr/lib64/glibc-hwcaps/x86-64-v3/libwebpdecoder.so.3.1.8</Path>

+ <Path fileType="library">/usr/lib64/glibc-hwcaps/x86-64-v3/libwebpdemux.so.2</Path>

+ <Path fileType="library">/usr/lib64/glibc-hwcaps/x86-64-v3/libwebpdemux.so.2.0.14</Path>

+ <Path fileType="library">/usr/lib64/glibc-hwcaps/x86-64-v3/libwebpmux.so.3</Path>

+ <Path fileType="library">/usr/lib64/glibc-hwcaps/x86-64-v3/libwebpmux.so.3.0.13</Path>

Let's rerun lld on dwebp after installing the new package and...

$ ldd /usr/bin/dwebp

linux-vdso.so.1 (0x00007ffeab5b1000)

libwebpdemux.so.2 => /usr/lib/glibc-hwcaps/x86-64-v3/libwebpdemux.so.2.0.14 (0x00007f9a351d5000)

libwebp.so.7 => /usr/lib/glibc-hwcaps/x86-64-v3/libwebp.so.7.1.8 (0x00007f9a3510b000)

libpng16.so.16 => /usr/lib/libpng16.so.16 (0x00007f9a350cf000)

libc.so.6 => /usr/lib/glibc-hwcaps/x86-64-v3/libc.so.6 (0x00007f9a34ed2000)

libsharpyuv.so.0 => /usr/lib/glibc-hwcaps/x86-64-v3/libsharpyuv.so.0.0.1 (0x00007f9a34ec1000)

libm.so.6 => /usr/lib/glibc-hwcaps/x86-64-v3/libm.so.6 (0x00007f9a34ddb000)

libz.so.1 => /usr/lib/glibc-hwcaps/x86-64-v3/libz.so.1.3 (0x00007f9a34dbb000)

/usr/lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 (0x00007f9a3520b000)

We can crucially see that dwebp is now loading the x86-64-v3 built libwebp.so lib from /usr/lib/glibc-hwcaps/x86-64-v3/libwebp.so.7.1.8, success! Let's what our performance looks like.

$ hyperfine "dwebp ~/3.webp -o /dev/null"

Benchmark 1: dwebp ~/3.webp -o /dev/null

Time (mean ± σ): 198.2 ms ± 1.2 ms [User: 195.4 ms, System: 2.5 ms]

Range (min … max): 197.0 ms … 200.5 ms 14 runs

$ hyperfine "cwebp ~/PNG_Test.png -o /dev/null"

Benchmark 1: cwebp ~/PNG_Test.png -o /dev/null

Time (mean ± σ): 1.313 s ± 0.009 s [User: 1.243 s, System: 0.078 s]

Range (min … max): 1.308 s … 1.341 s 10 runs

Let's recap so far:

| Optimization | Decode | Encode | Size |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 202.2 ms | 1.399 s | 1.33 MB |

| Speed + LTO | 200.0 ms | 1.353 s | 1.73 MB |

| Speed + LTO + PGO | 204.1 ms ⚠️ | 1.349 s | 1.07 MB |

| Speed + LTO + x86_64-v3 | 198.2 ms | 1.313 s | 3.17 MB |

Whilst we're still getting an additional speedup it isn't really anything to write home about. A measly ~2% improvement in decoding performance and a fairly respectable ~7% improvement in encoding performance for our test case. However, increasing the package size by an extra ~2MiB from providing a bunch of extra libs in /usr/lib/glibc-hwcaps/x86-64-v3/ just ain't worth it. This hints that either the compiler optimizations aren't really effective here or we're being bottle-necked by something else.

So far, we've been benchmarking fairly simply using hyperfine, let's swap that out for perf so we can get a callgraph.

Something about perf to the rescue

perf record -o dwebp.data -- dwebp ~/3.webp -o /dev/null

perf record -o cwebp.data -- cwebp ~/PNG_Test.png -o /dev/null

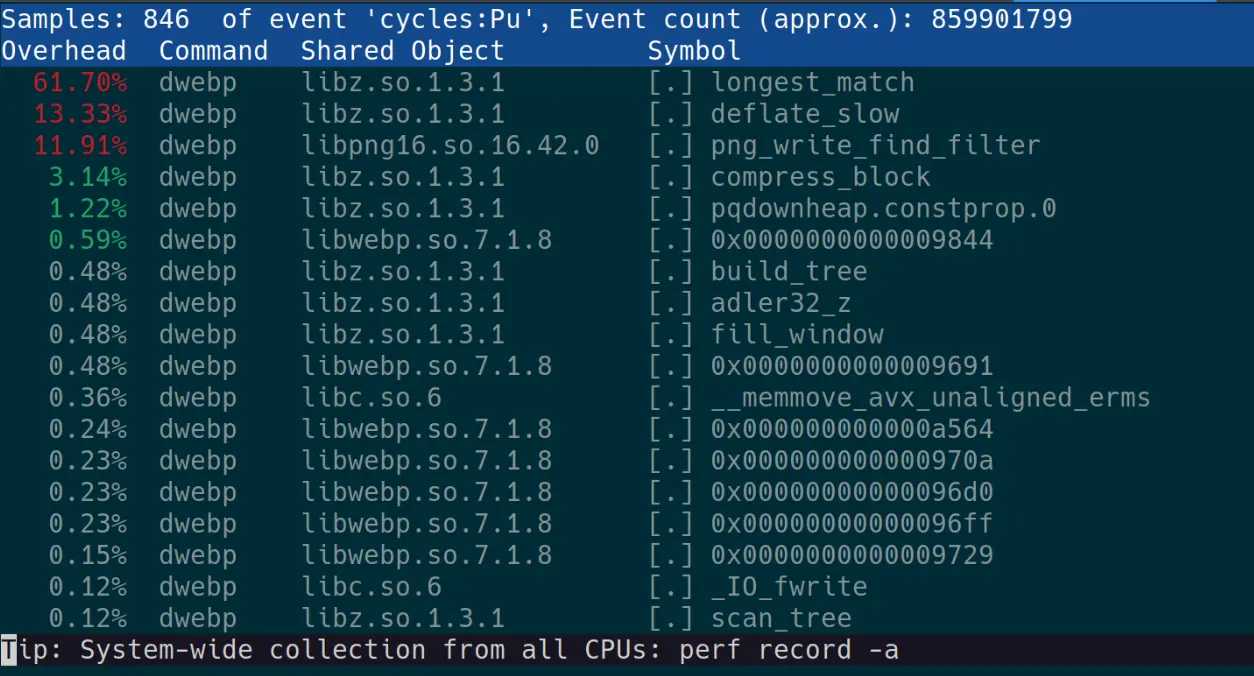

Let's look at dwebp first with perf report -i dwebp.data.

Well god damn, literally all of our time is being spent in libz.so it's no wonder our compiler optimizations were hardly improving performance.

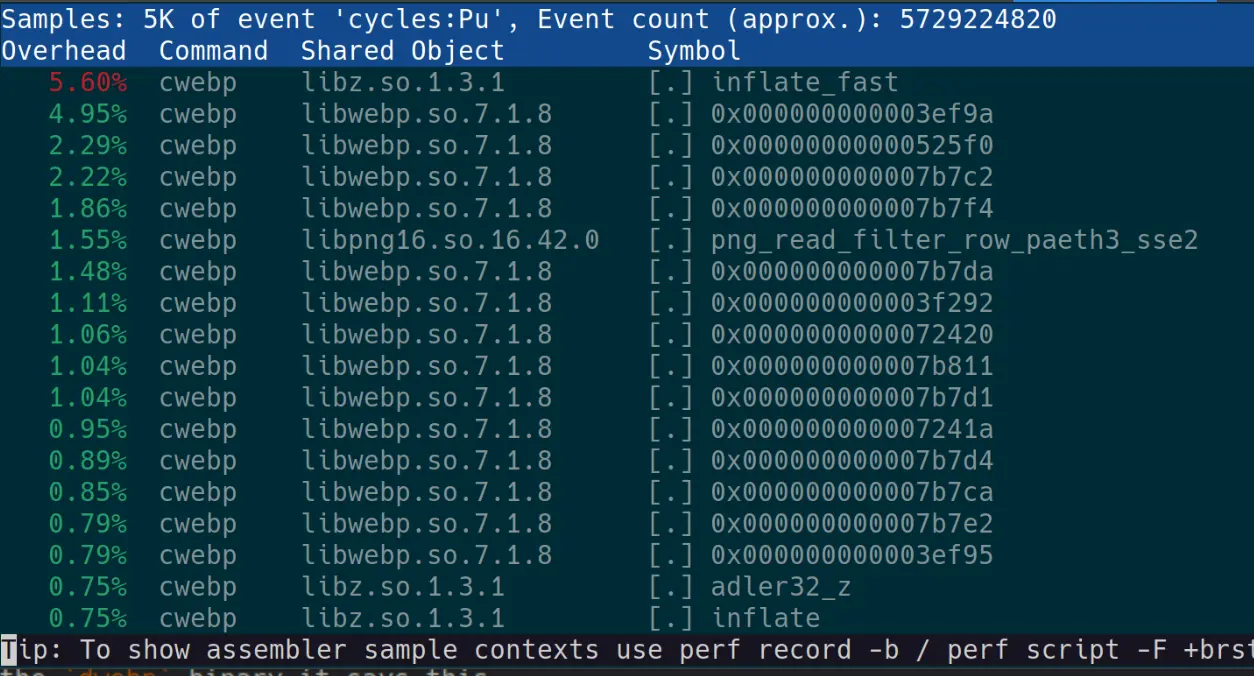

Let's also look at the cwebp report, we've generally been getting better results from it.

Okay, much more of our time is being spent in libwebp.so itself here which helps to explain why we were seeing a better performance uplift. Still 5.68% of our time is being spent in libz.

Choosing Wisely

You may remember early on, when I said we are also indirectly testing libpng. Well... after some more digging, that's exactly what's happening here. Re-running the dwebp binary it says this

Decodes the WebP image file to PNG format

Turns out, it's more accurate to say we are directly testing libpng and by extension zlib. It isn't libwebp that's spending all of its time in libz.so, it's libpng! This is exactly the reason you have to be careful about the benchmarks chosen and, ensure you understand what they're doing.

However, the good news about this little snafu is:

dwebpcan be used to translate to another image format such as.yuvthat'll more accurately remove the bottleneck fromlibz.so.- We now know that

libpnghas a huge bottleneck inlibz.soand speeding upzlibshould dramatically speed uplibpngperformance.

Adjusting the Benchmark

After reverting the libwebp package to the baseline let's use our adjusted decoding benchmark.

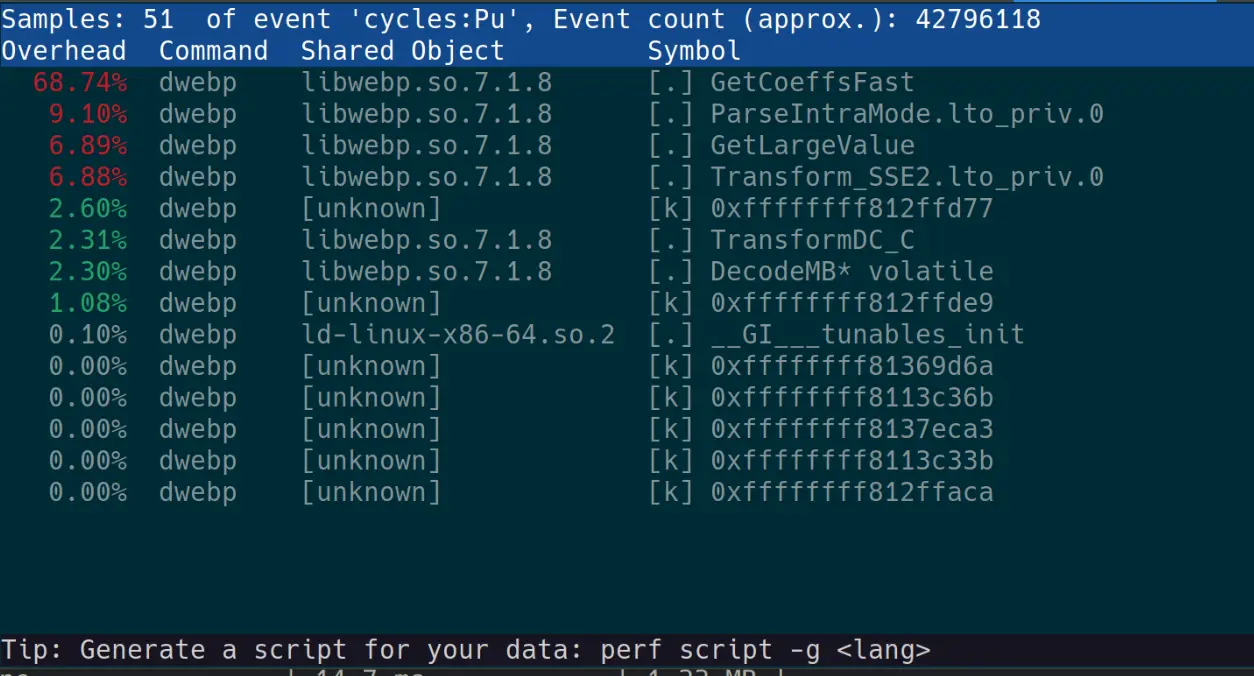

We'll now use dwebp ~/3.webp -yuv -o /dev/null for a decoding test, let's run that with perf to ensure we're exclusively testing libwebp.so here.

Okay that's awesome, no libpng.so or libz.so to mess with our tests!

Let's reapply our optimizations, keeping those which apply an uplift

| Optimization | Decode | Size |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 14.7 ms | 1.33 MB |

| Speed | 14.5 ms | 1.56 MB |

| LTO | 14.6 ms | 1.40 MB |

| PGO | 18.0 ms ⚠️ | 1.07 MB |

| x86-64-v3 | 12.7 ms | 2.35 MB |

| Speed + LTO + x86-64-v3 | 12.3 ms | 3.17 MB |

Okay, this is great, whilst we aren't getting much from speed or LTO, we are getting a big uplift from x86-64-v3 libraries and when combined with the other optimizations we're getting an uplift in performance of around ~16% at the cost of close to thrice the installed package size.

Partial Profiling

Once again we see that PGO regresses performance hard, however, that smaller size is giving a good hint! We already know that the profiling workload we gave it isn't very comprehensive due to the bunch of -Wmissing-profile warnings we get during the optimized build. By default, PGO will aggressively inline and apply additional optimizations to code that's part of the profiling workload while everything else will be optimized for size. The idea being, hot-path code is fast and code that doesn't matter is small. However, what happens when you can't craft a comprehensive workload, as seems to be the case here? Luckily GCC has a flag for exactly that -fprofile-partial-training. GCC docs state that:

In some cases it is not practical to train all possible hot paths in the program. (For example, program may contain functions specific for a given hardware and training may not cover all hardware configurations program is run on.) With -fprofile-partial-training profile feedback will be ignored for all functions not executed during the train run leading them to be optimized as if they were compiled without profile feedback. This leads to better performance when train run is not representative but also leads to significantly bigger code.

Okay, let's try it out, all we need to do is specify in our package.yml recipe.

environment: |

if [[ -n ${PGO_USE_BUILD} ]]; then

export CFLAGS="${CFLAGS} -fprofile-partial-training"

export CXXFLAGS="${CXXFLAGS} -fprofile-partial-training"

fi

And the results:

| Optimization | Decode | Size |

|---|---|---|

| Speed + LTO + x86-64-v3 | 12.3 ms | 3.17 MB |

| Speed + LTO + x86-64-v3 + Partial PGO | 12.5 ms | 3.13 MB |

Well, it was worth a try. This highlights how useless PGO can be when you don't or can't provide it a good workload. Interestingly, we don't get the size bloat that was promised, in fact, the opposite.

Final libwebp Results

| Benchmark | Time Before | Time After | Size Before | Size After |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| "dwebp ~/3.webp -yuv -o /dev/null" | 14.5 ms | 12.3 ms | 1.33 MB | 3.17 MB |

| "cwebp ~/PNG_Test.png -o /dev/null" | 1.399 s | 1.313 s | -- | -- |

In the end, we get a very healthy ~16% improvement in decoding from a .webp to .yuv file. As well as a respectable 6% improvement in encoding from a .png to .webp file. However, the increased package size is very unfortunate. It's possible to tweak the x86-64-v3 build and only ship the libs that actually improve performance in order to get the installed size back to an acceptable level.

"Next-Generation" Side Quest

Now, you probably remember earlier due to our unrepresentative benchmark we found out that libpng is getting highly bottlenecked by libz.so. This now seems like a perfect opportunity to take a look at zlib and circle-back to our original benchmark that we were using.

Zlib is widely employed throughout the ecosystem and, as such you'd think it would be highly-optimized for performance. However, that isn't really the case. Zlib is written in an old-fashioned way of C and tries to be extremely portable; supporting dozens of systems that have fallen out of common use. As such, it's hard to apply architecture specific optimizations that wouldn't break some old system or without introducing code spaghetti. There have been a couple of attempts to merge AArch64 and x86_64 optimizations into the canonical zlib library without success.

However, there is some light in this tunnel as various forks of zlib having been popping up, applying new optimizations on top of zlib. The most promising of these looks be to zlib-ng. When built in compatible mode, it promises to be API compatible with canonical zlib and tries to be as ABI compatible as possible.

Let's just go for it, replacing Solus' zlib package with zlib-ng built in compatible mode. It's a bit scary due to how integral zlib is in a typical Linux install, but, how hard could it be?

I Zee a Purty lil' Package

Well that was simple. Here's what our zlib-ng package.yml recipe looks like.

name : zlib

version : 2.1.5

release : 28

source :

- https://github.com/zlib-ng/zlib-ng/archive/refs/tags/2.1.5.tar.gz : 3f6576971397b379d4205ae5451ff5a68edf6c103b2f03c4188ed7075fbb5f04

homepage : https://github.com/zlib-ng/zlib-ng

license : ZLIB

component : system.base

summary : zlib replacement with optimizations for next generation systems.

description:

- A zlib data compression library for the next generation systems. ABI/API compatible mode.

devel : yes

emul32 : yes

setup : |

%cmake_ninja \

-DZLIB_COMPAT=ON \

-DWITH_GTEST=OFF \

-DBUILD_SHARED_LIBS=ON \

-DINSTALL_LIB_DIR=%libdir%

build : |

%ninja_build

install : |

%ninja_install

check : |

%ninja_check

After building it, all the files seem to be in the right place and the test suite is passing. Let's just install it overwriting our canonical zlib package and hope our system doesn't die... I think the word is YOLO.

$ hyperfine "dwebp ~/3.webp -o /dev/null"

Benchmark 1: dwebp ~/3.webp -o /dev/null

Time (mean ± σ): 198.6 ms ± 2.3 ms [User: 194.3 ms, System: 3.6 ms]

Range (min … max): 196.3 ms … 203.3 ms 14 runs

$ sudo eopkg it zlib-2.1.5-28-1-x86_64.eopkg

...

$ $ hyperfine "dwebp ~/3.webp -o /dev/null"

Benchmark 1: dwebp ~/3.webp -o /dev/null

Time (mean ± σ): 87.6 ms ± 0.7 ms [User: 84.7 ms, System: 2.6 ms]

Range (min … max): 86.5 ms … 88.7 ms 33 runs

Well, hot diggity damn. Swapping out the zlib package for a more performant variant has instantly more than halved(!!) our decoding time.

We need to find a more contained libpng benchmark here that removes the libwebp stuff to really confirm the findings here. After some sleuthing the libpng source repository has a pngtopng.c file we can compile to use the system libpng library.

Changing the header from #include "../../png.h" to #include <png.h> then running gcc -Ofast pngtopng.c -lpng16 -o pngtopng to compile it, we have a libpng benchmark. We can reuse our test .png file from earlier. Ending up with: ./pngtopng ~/PNG_Test.png /dev/null for our benchmark.

| Library | Time |

|---|---|

| zlib (canonical) | 1.464 s |

| zlib-ng (compat) | 896.6 ms |

Well. This is pretty much inline with our flawed dwebp benchmark from earlier. Swapping out zlib almost halves libpng decoding time.

Squeezing more from zlib-ng

However, we're not done yet. We still have our compiler optimizations available to us to squeeze more performance from zlib-ng.

| Optimization | Decode | Size |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 896.6 ms | 141.00 KB |

| Speed | 883.6 ms | 182.00 KB |

| LTO | 892.7 ms | 133.00 KB |

| PGO | 894.6 ms | 141.00 KB |

| x86-64-v3 | 892.5 ms | 295.00 KB |

| Speed + LTO | 882.6 ms | 170.00 KB |

| Speed + LTO + PGO + x86-64-v3 | 882.5 ms | 250.00 KB |

It looks like in this case the simple speed + LTO optimizations is the way to go. Speed gives the majority of the speedup but LTO helps bring back down the package size again. However, it's only a 1.5% improvement from baseline for this benchmark. We can always re-benchmark it later, testing zlib performance more directly instead of via libpng. It shows how good a job the zlib-ng developers have done that it's so performant right out of the gate.

Final Words

We've shown the process of how a package can be optimized in Solus, through the failings and wins here I hope some good tips and tricks were provided in avoiding common pitfalls. Additional benchmarking strategies such as BOLT or Polly optimizations were not discussed and it'll be good material for a future blog post.

Some other important things such as tweaking the system for benchmarking in order to get representative and consistent results were also not discussed. This is especially important in power budget constrained systems such as laptops and worth bearing in mind.

Regardless, I hope the story of how libwebp was optimized for was entertaining and some things were learnt for anyone looking to optimize packages in Solus for the future.